Jump to:

Racial Terror Lynchings in Orange County, NC

1898 – About Manly McCauley

Preface: Historical Context

Haunted by white terrorism: We don’t know most of their names. Those who were murdered, those who were raped, those who were whipped and beaten, both publicly and in their homes. Nor do we know the names of the churches that were burned to the ground, or the schoolhouses that were destroyed. We do know, though, that in the years following Emancipation—and particularly in those years between the 1868 N.C. Constitutional Convention (which proclaimed Black men’s right to vote and created the state’s first public school system for African Americans and whites) and 1870 (when the Conservative party regained control of the N.C. state government)—white terrorism haunted the Black experience in Orange County.

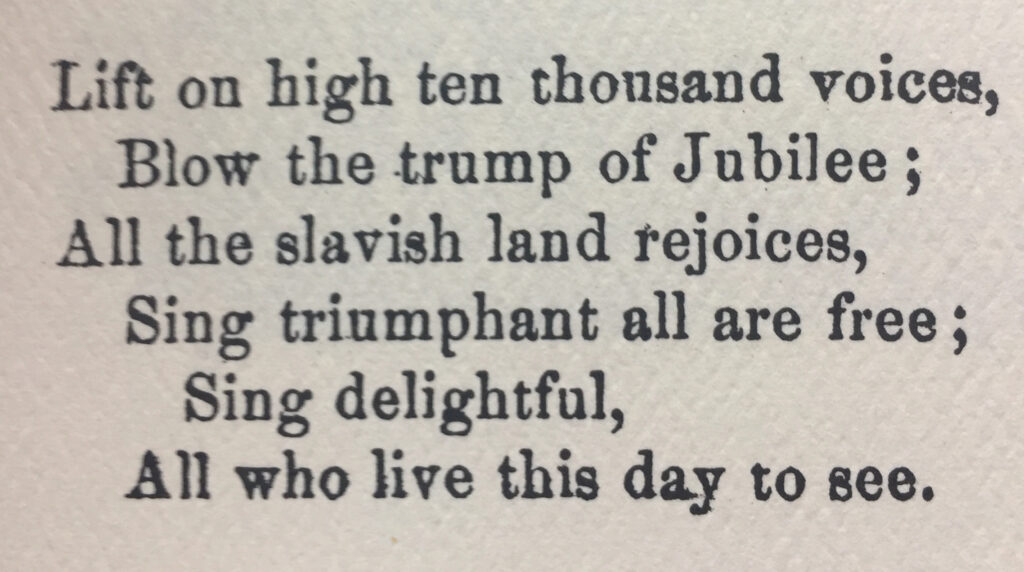

Chapel Hill’s peerless Black poet, George Moses Horton, captured the sense of jubilation that swept through Orange County’s African American communities with the arrival of Union troops in this stanza from his 1865 poem, “Song of Liberty.” (From Horton’s Naked Genius)

Emancipation: Emancipation had been a time of jubilation for African Americans in Orange County, marked by bonfires, parades, and exuberant public meetings. It was also a long-awaited time of self-determination, as formerly enslaved farmers, cooks, tradespeople, and houseworkers seized every opportunity to establish their own churches, create community schools, exercise their newfound political power, and join together to resist economic exploitation. The county’s thousands of Black residents passionately claimed agency over the narratives that had been told about them, publicly declaring their humanity in ways that had long been denied. Songs rose with more exuberance; hairstyles emerged with declarative spirit; clothes sparkled with color and drama; and Black voices claimed the soundscapes of town and countryside. Each such act of affirmation proclaimed Black humanity. And each such act challenged white claims of superiority, threatening a social order that had been built on Black subservience.

White backlash: In those same years, the forces of white supremacy in Orange County were doing everything in their power to resist these affirmations and to maintain control. Plantation owners devised new forms of enslavement; white townspeople passed laws restricting Black movement and political advancement; white merchants choked off opportunities for Black commercial growth. The local landscape changed, however, in 1868, when Black men gained the right to vote. The next election filled most Orange County offices with officeholders loyal to the party of Lincoln. Their numbers included a Black justice of the peace and a Black police officer.

The Klan: It didn’t take long for angered white elites in the county to respond. They hastily organized a local order of the Ku Klux Klan, which immediately began parading on horseback through the streets of Chapel Hill. A regime of supremacist violence soon exploded across the county. By September 1869, Raleigh’s Weekly Standard newspaper declared, “A reign of terror hangs over the loyal citizens of the County of Orange.” Two years later, when speaking of this period before a Senate committee, Chatham County Black farmer Essie Harris testified, “I have heard tell constantly of the burning of school-houses and meeting-houses,” noting that the targeted “meeting-houses” were places where Black children were being taught to read and write. “I hear tell of whippings every week,” he later added.

Shortly after the county’s first documented lynching, white townspeople in Chapel Hill ardently declared their endorsement of Klan violence, passing a resolution that pointedly refused “to condemn good citizens and true men who in self-defense resort to other means because they fail to obtain from the law that protection and security which they have a right to demand.” Sowing seeds of fear, while claiming that the law no longer served “true [white] men,” local white supremacists endorsed—and invited—violence against African Americans.

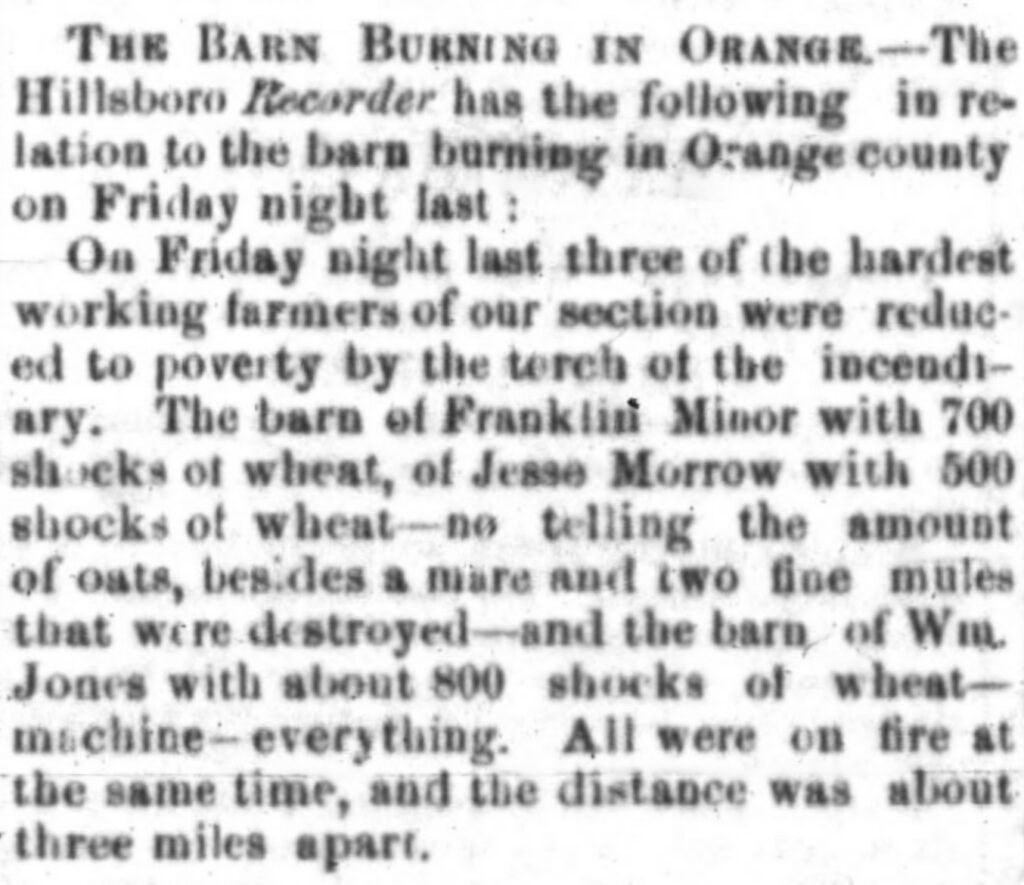

Black resistance against terror: Black residents of Orange County, in turn, organized their own resistance movement, one that perhaps became most publicly evident in the burning of barns on white-owned farms. Many plantation owners who refused to accept the realities of emancipation had “hired” the families whom they had once enslaved to continue working their farms. After the fall harvest, however, they often refused to pay these Black workers, or declared that their families had closed the year in debt and thus would have to stay on for another planting season. Challenges to the plantation-owner’s claims, or even attempts to move away from the farm, were typically met with violence. Faced with little legal recourse, some Black resistors chose to respond by striking directly at white wealth, setting plantation-owners’ food-storage and livestock barns afire. Three of the Orange County men lynched in 1869 were blamed by their murderers with barn-burning, even though no evidence actually connected any of them to the fires.

Three simultaneous barn burnings in July 1869 put Orange County’s white farmers on edge, forcing them to recognize that Black workers were now acting together to battle white supremacy. With little delay, white residents—fueled by sensationalistic newspaper articles like this one—began capturing, beating, jailing, and lynching African American “suspects.” (From The Daily Sentinel, July 28, 1869)

Unnamed, uncounted victims of lynching: We know the names of five—and perhaps six—of the Black men murdered in Orange County in 1869. We don’t know, however, how many others died at the hands of white supremacists during this period. In his 1871 testimony before a Senate committee, Dr. Pride Jones—an ex-Confederate officer whom the governor had commissioned to disband the Orange County Klan—recounted five lynchings in the county. More than half a century later, African American elder Ben Johnson—who himself had been enslaved in Orange County—described a terror attack that Jones didn’t include in his tally, recounting how masked klansmen had burst into the home of a Black farming couple, dragged them into the woods, beaten them, and then thrown their bodies into an ice-covered pond. The husband, identified only as Ed, was able to pull himself out; his wife, Cindy, was not. Mr. Johnson also recalled the 1869 lynching of a Mr. Joe Turner, a name that never appears in any other historical account. Contemporary family stories tell of additional Orange County lynchings that don’t fit the details captured in local news accounts. Together, these stories convincingly point to more than five racial terror murders.

Named and honored: Below, though, are the five names that we know. Their stories are tragically thin, as most of our knowledge of their lives comes from the skewed accounts of their deaths, as captured in white newspapers. Their voices, their laughter, their loves, their talents, their hopes remain hidden to us, leaving us to imagine the fullness of their lives. With each such imagining, we grieve their loss, and honor their presence . . .

Source Information

- John K. (Yonni) Chapman. Black Freedom and the University of North Carolina, 1794-1960. Ph.D. Dissertation, Dept. of History, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2006.

- Found Hanging. The Daily Standard, Sept. 22, 1869, p. 2.

- Essie Harris. In Report of the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, Made to the Two Houses of Congress, February 19, 1872, pp. 86-102. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1872.

- Ben Johnson. In A Folk History of Slavery in the United States from Interviews with Former Slaves. Vol. XI: North Carolina Narratives, Part 2, pp. 8-13. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1941. https://www.loc.gov/resource/mesn.112/?sp=12

- Pride Jones. In Report of the Joint Select Committee to Inquire into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States, Made to the Two Houses of Congress, February 19, 1872, pp. 1-13. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1872.

- Ku Klux Outrages. The Weekly Standard, Sept. 29, 1869, p. 3.

- Pauli Murray. Proud Shoes: The Story of an American Family. New York: Harper, 1956.

- Public Meeting. The Semi-Weekly Sentinel, Sept. 29, 1869, p. 2.

Jump to:

Preface: Historical Context

Racial Terror Lynchings in Orange County, NC

1898 – About Manly McCauley

Racial Terror Lynchings in Orange County, NC

Washington Morrow

August 8, 1869

In the early morning hours of August 7, 1869, a masked mob of klansmen assaulted the county jail in Hillsborough and pulled out two young Black men—20-year-old Nelson Morrow and his 19-year-old brother Washington—who had been jailed the previous month on suspicion of burning the barns of three prominent white farmers. The crowd of mounted and robed klansmen took the two brothers about a half-mile out of town, where they questioned them and then ultimately let them go, with the mob’s leader allegedly declaring they he wasn’t convinced the two Black men were the guilty parties.

As the brothers ran into the woods, however, they were met with a fusillade of bullets from the klansmen. Washington Morrow was struck in the thigh, while Nelson escaped unhurt. He helped his brother into the woods and then into a nearby field, where they spent the night hiding in a haystack. The next morning, Nelson Morrow ran back into town to notify the sheriff, who had a wagon carry the wounded Washington back to the jail. That night in the field ultimately proved fatal, however, and Washington Morrow died soon thereafter, the county’s first documented victim to Klan violence.

Washington and Nelson Morrow were the oldest children of Jefferson and Lucinda Morrow, in a family that included three other sons and three daughters. Both brothers had grown up in enslavement, and had likely continued living with their family until a year or so before their arrest, at which point the two had moved to sharecrop on a neighboring white-owned farm. Shortly after the brothers had moved, the rest of the Morrow family was forcibly evicted from the farm on which they had been laboring—with no cause given other than the farm-owner’s decision. That white farmer’s barn was one of those that later went up in flames, along with that of the plantation owner whom had enslaved the Morrows. It was these connections that gave rise to the charges against the Morrow brothers.

Tellingly, the only public notice of Washington Morrow’s death came in a terse, ten-word note in the Hillsborough newspaper, sandwiched between a sentence noting a recent rainfall and another listing the current cost of corn. It wasn’t until more than two months later, immediately following the lynching of the Morrow brothers’ father and uncle, that Governor William W. Holden issued a proclamation threatening military action against violent supremacists, noting that, “In Orange the jail has been forcibly opened and two prisoners (colored men) taken out and shot, one of whom has died from his wounds.” Three months later, on the eve of Nelson Morrow’s trial on the charge of barn-burning, the judge in that case denounced the fact that one of the men taken from the jail—a still-unnamed Washington Morrow—had been “murdered in cold blood not far from the town.” After spending six months in jail, Nelson Morrow was acquitted of the crime for which he had been charged, and for which his younger brother had been killed.

Wright Malone

September 6, 1869

Historical records aren’t kind to the memory of Wright Malone, leaving little evidence of his life. We do know, however, that he was a young Black farmer who likely lived with his parents and three siblings (the youngest of whom was only eleven) on a farmstead near the banks of the Little River, in the eastern part of Orange County. Mr. Malone spent his childhood in enslavement, living in a household where the parents were claimed by two different white enslavers. Those parents—Malinda and Squire Malone—formalized their longstanding marriage immediately after Emancipation.

On the evening of Sept. 6, 1869, Wright Malone was helping his father fire the family’s charcoal kiln—usually an all-night affair—when four masked white men showed up on horseback with pistols drawn. They bound the young Malone and rode away with him, telling his father that they were carrying him to the Hillsborough jail. The worried father later rode into Hillsborough, hoping to bring his presumably incarcerated son some food, only to discover that his Wright Malone had never made it to the jail. Six days later, a neighbor discovered Wright Malone’s body hanging from a tree not far from the family’s home.

Newspaper reports of this lynching identified the victim as Wright Woods, using the surname of the white family that had enslaved Wright Malone and his mother. The Coroner’s Inquest, however, uses the name Malone, the surname of Wright Malone’s father, and also that name that the family had adopted after formally registering their marriage in 1866.

By all accounts, Wright Malone’s lynching was the first hanging attributed to the Klan in Orange County. Evidence gathered by the county coroner suggested that the murder—like the jail assault of the previous month—had been carefully planned in advance.

Daniel Morrow & Thomas Jefferson Morrow

October 14, 1869

Two months after the August murder of Washington Morrow, and while his brother Nelson remained in jail charged with barn-burning, the Klan once again targeted members of the Morrow family. This time, the mounted mob attacked the homes of both Thomas Jefferson and Lucinda Morrow—the Morrow brothers’ parents—and Daniel and Sally Morrow—the brother and sister-in-law of Lucinda Morrow. At Jefferson and Lucinda Morrow’s farmhouse, the nighttime attackers shot into the structure and then kicked down the door; at Daniel and Sally Morrow’s home, they demanded that he open the door and then grabbed him when he did so. The children in both homes were terrified by the armed and robed klansmen, who dragged their fathers into the yard and then out across the fields.

Thomas Jefferson Morrow was in his early 40s when the Klan attacked his home; he lived there with his wife Lucinda and six children, the youngest of whom was a baby at the time. Daniel Morrow—Jefferson Morrow’s brother-in-law—was likely in his late 30s at the time, and was living with his wife Sally, their four children (including one just recently born), and his elderly mother.

According to wrenching testimony that Lucinda Morrow gave at Governor William Holden’s impeachment trial seventeen months later, her husband pleaded with his attackers to at least let him say goodbye to his children. The klansmen responded with curses and threats, and then dragged him outside. That was the last time the family saw Thomas Jefferson Morrow alive.

Fearing that the mob would return later that night, Lucinda Morrow took the children into a nearby field, where they spent the night. The next morning, she and her sister-in-law Sally, both accompanied by their oldest daughters, set out to find their husbands. They found them about a half-mile from Thomas Jefferson and Lucinda Morrow’s home, each hanging from trees about 25 feet apart. Lucinda Morrow reported that a piece of paper was pinned to her husband’s breast, bearing the words, “All barn-burners, all women offenders, we Kuklux hang by the neck till they are dead, dead, dead.”

In her testimony at Gov. Holden’s 1871 impeachment trial, Lucinda Morrow fearlessly named four of the disguised men who lynched her husband, saying that she recognized their voices and their clothes; she further affirmed her certainty by noting that she had been “been always raised with them.” Not surprisingly, none of those men was ever charged with the murder of the Morrows.

In response to the shooting of Washington Morrow, and to the subsequent lynchings of Wright Malone, Daniel Morrow, and Thomas Jefferson Morrow, the Republican Governor William W. Holden threatened to designate Orange and three other counties in “a state of insurrection” and to take decisive steps to restore the rule of law. Holden’s proclamation met with derision in the supremacist press, which insisted on describing the Morrows as barn-burners and their murderers as taking “justified” action in the absence of meaningful response by the state. Holden ultimately decided to declare Caswell and Alamance county “in insurrection.” This declaration began what became known as the Kirk-Holden War, pitting forces friendly to Governor Holden against the Klan and their allies, and ultimately leading to Governor Holden’s 1870 impeachment by a Democrat-dominated General Assembly.

Cyrus Guy

December 1, 1869

Cyrus Guy was a 24-year-old Afro-Indigenous farmer who had never been enslaved, having grown up in a family listed as “free persons of color” since the early 1800s. Though details about his early life are slim, Cyrus Guy—called “Cy” by family and friends—had likely grown up just across the Orange County line in Alamance County, where his farming parents, Walter and Kiziah Guy, two younger sisters, and two younger brothers still lived at the time of his death. At some point in the late 1860s, the young Guy moved into Orange County, where he found work on a farm northwest of Hillsborough.

Somewhere around the first day of December in 1869, a mob of masked klansmen—later described by Black elder Ben Johnson as “more than a hundred strong”—seized Cyrus Guy and carried him into the woods on the High Rock Road, just above the Orange County Poorhouse. The 85-year-old Ben Johnson—who grew up enslaved near Hillsborough, and who offered his testimony to a WPA interviewer in 1937—recalled the murder vividly, asserting “I never will forget when they hung Cy Guy.” The alleged offense—as was so often the case with racial terror lynchings—was “a scandalous insult to a white woman,” and the predetermined sentence was death.

“They tried him there in the woods,” Mr. Johnson recalled, “and they scratched Cy’s arm to get some blood. And with that blood they wrote that he shall hang ‘between the heavens and the earth till he is dead, dead, dead,’” adding that anyone who dared to “take down the body shall be hanged too.”

“Nobody would bother with that body for four days,” Mr. Johnson remembered, even though the body was hanging “right over the road . . . . And there he hung, swinging in the wind.” Finally, the sheriff had the body taken down, and appointed an interim coroner to determine the circumstances of Mr. Guy’s death. Not surprisingly, the coroner’s report declared that Mr. Guy had been murdered “by persons unknown.”

Jump to:

Preface: Historical Context

Racial Terror Lynchings in Orange County, NC

1898 – About Manly McCauley

Compiled by Glenn Hinson, Assoc. Professor of Anthropology and American Studies, UNC. With special thanks to Iman Amadou, Student Researcher, UNC; Mark Chilton, Orange County Register of Deeds; Sally Greene, Independent Scholar & Commissioner, Orange County Board of Commissioners; Madison Holt, Student Researcher, UNC; Seth Kotch, Assoc. Professor of American Studies, UNC; Molly Luby, Community History Coordinator, Chapel Hill Public Library; Deborah Patrice-Hamlin, Founder & CEO, BronzeTone Center for Music & History; James Williams, Attorney, Founder & Chair, North Carolina Commission on Racial and Ethnic Disparities; and the UNC Descendants Project.

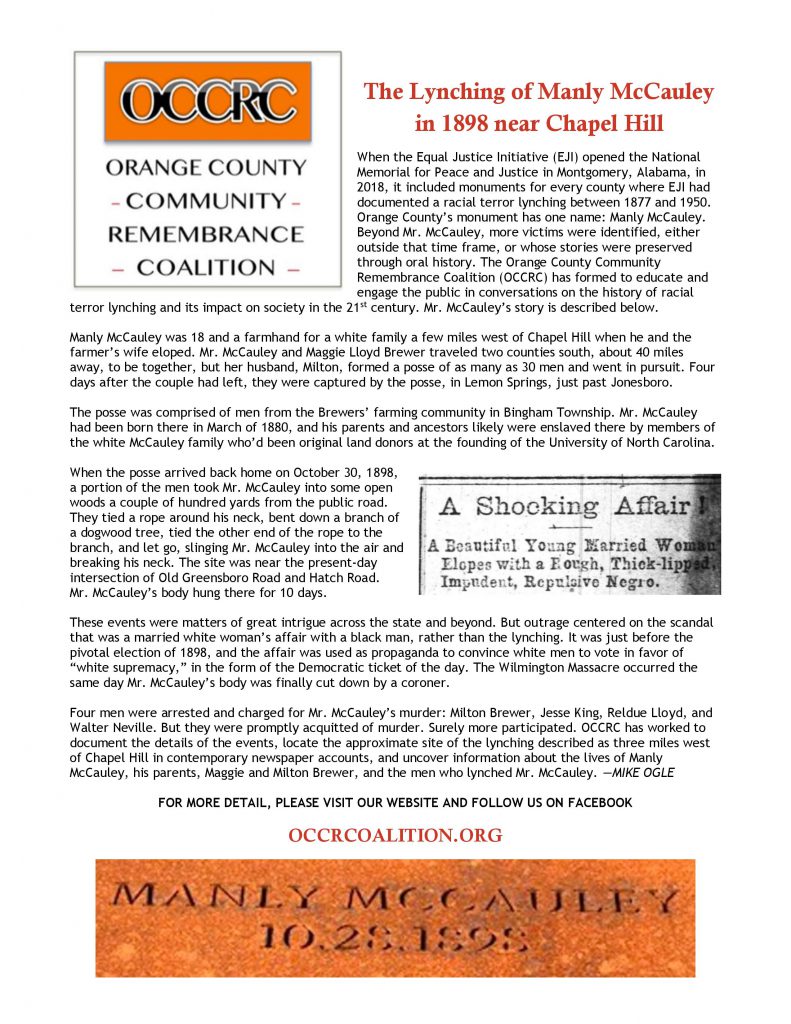

1898 – About Manly McCauley

Manly McCauley was lynched at 18 years old by a mob of white neighbors in October of 1898, just before a pivotal election, for his affair with a married white woman. This leaflet below provides a brief synopsis of what transpired.

And at this link, find a more detailed narrative of events, Manly McCauley’s life, and other connected people.

Jump to:

Preface: Historical Context

Racial Terror Lynchings in Orange County, NC

1898 – About Manly McCauley